Professor Peter Beverley is a well-respected figure in the field of immunology research.

During his career he has been involved in over 300 research publications and has over 19,000 citations. He created many different antibodies throughout his career at the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (ICRF), many of which are now commercialised through Ximbio.

At present, Ximbio has 17 of Peter’s reagents in its portfolio, including the highly popular UCHT1 and UCHL1 antibodies against well-known universal T-cell marker CD3 and memory T-cell marker CD45RO respectively.

With such a distinguished career, we wanted to discover what it felt like to create UCHT1 and UCHL1, what he was most proud of in his career and how the life sciences industry has changed.

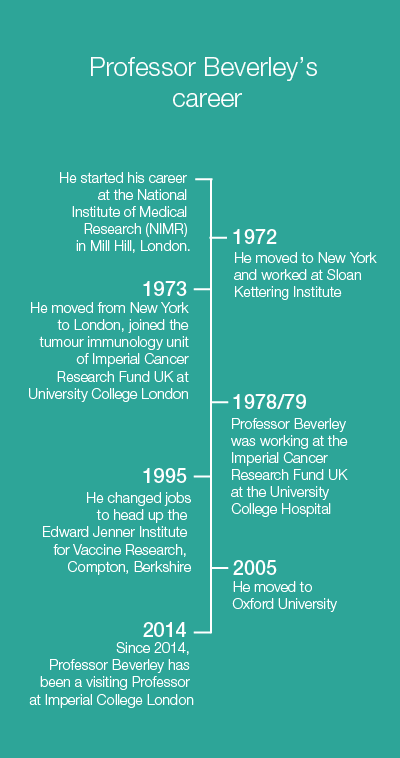

Tell us about your career

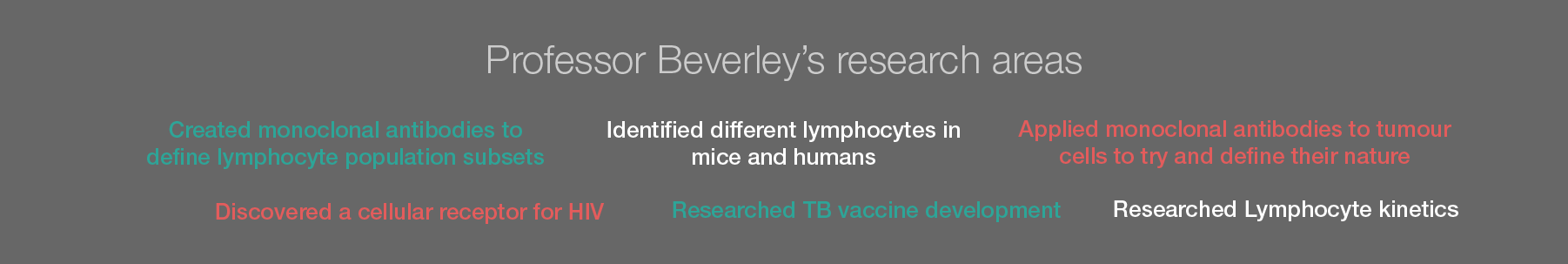

"I started my career working at Mill Hill (Medical Research Council laboratories) and was then offered a job at Sloan Kettering, a large cancer research institute in New York. So, I went to do my Post-Doc there and work on lymphocytes. I ended up working mostly on mouse immune responses in general – not just cancer related - and whilst I was there I started to identify different sorts of lymphocytes.”

“When I came back to London from New York, it was initially to work in mice and do the same sort of things - to define how blood cells work and what they all do. I worked for ICRF and was based at University College London (UCL). After a few years we decided to set up an offshoot of the immunology unit in the medical school of UCH. This unit aimed to define different sorts of human lymphocytes and to apply that knowledge to cancer and immune therapy. At the time there wasn’t much you could do in this field, but we thought we should try to apply these technologies to tumours in humans. That offshoot was called the human tumour Immunology group (HTIG).”

“In the late 1970s, I started to make monoclonal antibodies and as part of this ended up making the famous UCHT1 and perhaps the even more famous UCHL1. Our laboratory was one of the first laboratories to start making monoclonal antibodies against lymphocyte cell surface markers.”

“At some point in the 1980s I got into HIV – partly because it was a really important disease in the 1980s and partly because UCH was a big centre in London for early HIV work. Colleagues there were very keen to collaborate with us, so we started to work on it late at night. We ended up discovering the cellular receptor for HIV.”

“I left ICRF in 1995 and joined the Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research where I did some very nice studies in humans on the kinetics of lymphocytes. It made people think a bit about the nature of immunological memory such as how we should best vaccinate. “

“Finally, the last thing I did in my career was work on vaccines for TB. And I think we contributed to that field as we were one of a few labs that really focused on local immunity to TB. We showed that local immunity in the lung - at least in mice, monkeys and cattle – is very important for protection against TB. The human vaccine field is now going that way and there are initial trials taking place into a TB vaccine that will be administered, probably as an aerosol into your lungs.”

What were your career highlights?

“I still remember seeing UCHT1 antibody working for the first time in a little dark room in the medical school. For some reason we were screening cells under a microscope for this particular fusion rather than using a cell sorter, I can’t remember why now, but I would put a few cells from a well on a slide and put them under the microscope under phase lighting to see the cells. I’d then switch to fluorescence and wonder are any of them going to fluoresce?”

“So, I was sitting there, in this dark room, and I had gone through, I don’t know about 100 wells or something, looking at these cells and wondering if they were going to fluoresce and nothing interesting came up. And then I reached the key one and oh! I’d seen 150 cells perhaps on the phase view and when I switched to fluorescence clearly some of them were not staining. I knew I’d got an antibody that was seeing a subset of cells and I knew it was going to be interesting. That was UCHT1 against CD3. In fact, in the same fusion there was UCHT4 (we labelled them just as we identified them), which was actually a CD8 antibody and so we had 2 very nice antibodies out of that particular fusion.”

“So those moments, you know, stay with you for a very long time. A lot of research is boring and things don’t work half the time – in fact we had an awful period after we had done our first hybridoma fusion to generate monoclonal antibodies and it stopped working. Nobody at that time was talking about mycoplasma contamination of cultures (which is what we ended up having), but they can completely screw things up. We stopped making hybridomas for about a year whilst we wrestled with this thing. So, you can have these long periods where nothing works and you make a whole load of mistakes. But, there’s always fun. There were these wonderful days where you would see something down the microscope and it’s terribly exciting. And then there are the occasionally real highs, like finding the receptor for HIV in 24 hours.”

“There is just a lot of very nice collaboration with very nice people all over the world, so that you end up having friends in Australia, in the States, in Holland. In my own case I suppose it’s been gratifying that some of these antibodies have really been useful.”

What was your proudest moment?

“Out of all the things I’ve done that I am proud of, one of my proudest achievements, is defining different types of lymphocytes – initially in 1975, in mice and then in similar experiments in humans.”

“In addition, defining naïve and memory cells was very important – the latter are those cells that have seen infection, and finding out how long they last, which had an impact on vaccine use. My UCHL1 anti-CD45RO reagent was very important for the world in defining memory and naïve cells.”

“Clearly finding the cell surface receptor, CD4, for HIV was a bit lucky in a way, but you need to have a prepared mind and do the right experiment. It is very seldom that you do an experiment that gives you the answer in 24 hours. So, this was an unusual experiment from that point of view. We did some additional confirmatory experiments after, but we didn’t really need to, as we knew the answer, which was amazing for such an important discovery. I made 50 CD4 antibodies after this for CRUK to discover exactly where on the molecule the HIV receptor was hiding.”

What motivates you?

“Well I don’t know, what does motivate you? There are always questions to answer and I personally very much enjoyed doing things in the lab. Although I had quite a large group when I was at Cancer Research UK of around a dozen people or so, I liked actually doing experiments.”

“I made a lot of the monoclonal antibodies myself because I enjoyed the cell culture and messing about with the cells. Looking at them down a microscope and running the cells through a screening - that was always fun you know, because you never knew quite what you were going to find when you screened the monoclonal antibodies.”

Discover how we can support you in commercialising your reagents, explore our current partnerships and discover Peter Beverley’s reagents: